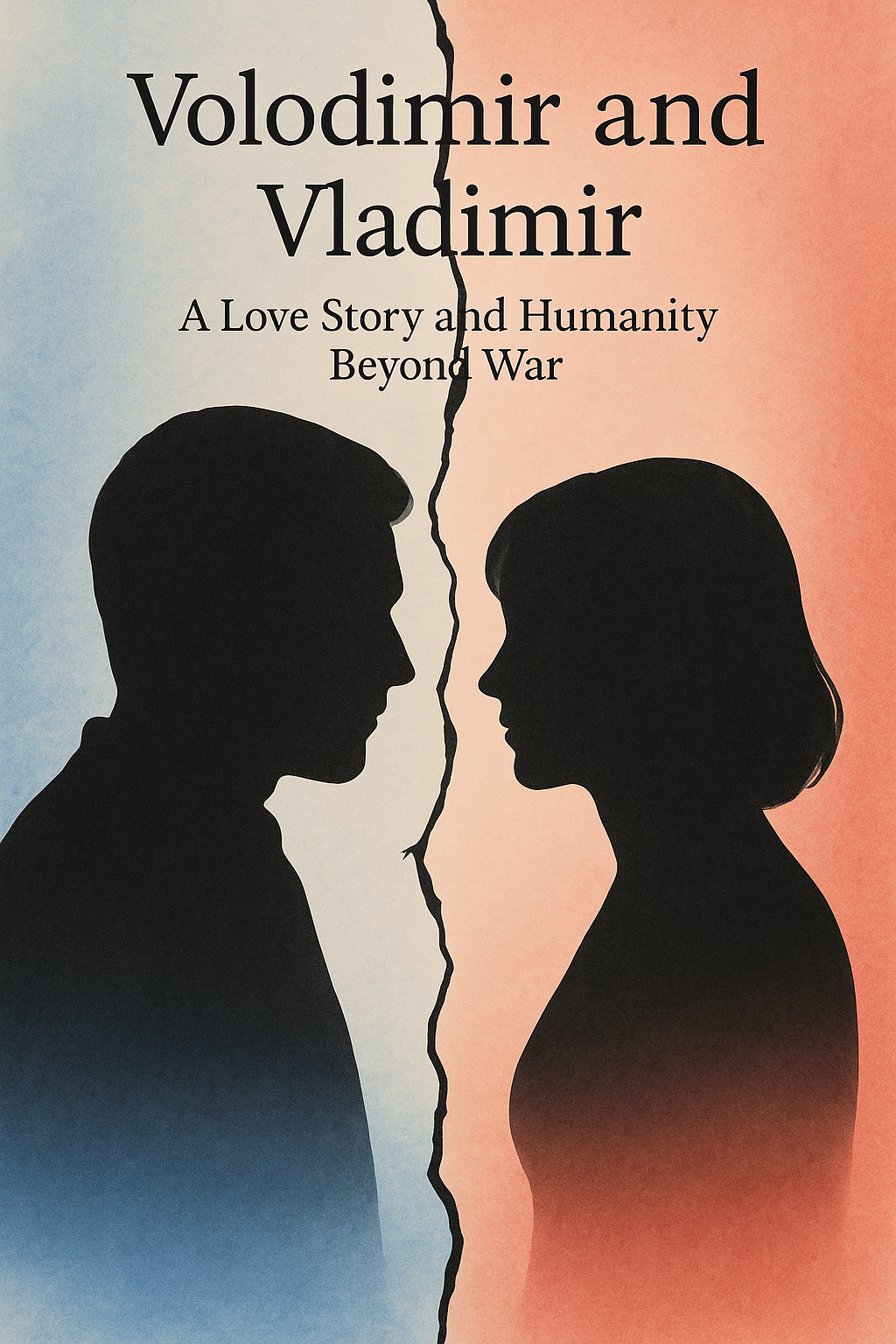

Volodimir and Vladimir

Translated from Hungarian by ChatGPT and the author.

This novella follows the love

story

of a Ukrainian IT engineer and a Russian woman under the shadow of war.

It explores not only the senselessness and brutality of conflict, but

also the power of human connection — how two lives can be transformed

in a world where survival comes at the cost of conscience. Love,

betrayal, and forgiveness intertwine, revealing what the world could

be… if it were different.

Human, beware – look closely at your world.

This was the past, this the raging present –

Carry it in your heart. Live through this

broken world,

And always know what must be done

To make it something else."

Miklós Radnóti, “He Could Not Bear It”

My name is Volodimir Piatkin. I’m twenty-nine years old – a descendant

of Cossacks who once gave their hearts and lives for freedom. At last,

I belong to the majority nation. I know our history is steeped in

suffering and struggle. Still, the first time I truly listened to the

Ukrainian national anthem as an adult, something unsettled me. The

military tone. The cult of blood sacrifice. The readiness to die. It

didn’t feel like a song praising life – it felt like a hymn to

destruction. And every time I hear it, my stomach tightens. But I love

my homeland. I do. I just don’t believe that the value of life can – or

should – be measured by the nobility of death.

My mouth is wide. Dunya’s is

narrow, full, and gracefully curved – lips that don’t thin out at the

edges like most people’s. Because of this, her expression often appears

severe, as though she were perpetually pursing her lips in quiet

irritation or silent anger. But she’s not angry. That’s just how her

mouth is shaped. It’s like Monica Bellucci’s lips – only thinner, more

sculpted. Its width barely stretches beyond the space between her tear

ducts, as if nature had precisely measured and fitted it there. Mine,

in contrast, runs nearly to the corners of my eyes. On that basis

alone, I might look like someone who’s always smiling. But I rarely do.

When I think, I lean forward, elbows on knees, hands clasped, eyes

fixed on nothing – as if trying to extract the hidden logic of the

universe from the vacuum before me.

Dunya, my dearest love, is

Russian by birth – but in every other way, she’s the archetype of

Slavic beauty: fair, blonde, composed. We first met during the

Euromaidan. If the government hadn’t collapsed… if the protests hadn’t

ignited… if Yanukovych hadn’t fled… I might never have met her. And so

I often ask myself: should I be grateful to Yanukovych for – however

indirectly – leading me to her? Or should I curse his name and send him

to rot in the deepest circle of Hell, alongside every puppet and thief

he stood with?

In November 2013, to my shock,

our president stepped away from the long-awaited Euro-Atlantic

integration deal. Everyone knew it was a pro-Russian move. And with

that, the avalanche began. What followed was a wave of resistance that

surged into full force in Maidan Square. Protesters occupied the

square, standing their ground peacefully but relentlessly, day after

day. Until January 16, 2014. That day, Parliament – like thunder from a

cloudless sky – passed a law by show of hands. A law that, in effect,

legalized dictatorship. Everyone knew what it meant: they were planning

to crush the protests. Anger exploded. Crowds flooded into Kyiv.

Resistance spread.

I arrived on February 20. The

train creaked into the station under a dry, icy light. It was minus

twenty Celsius. As we stepped off, our breath burst in soft, white

clouds.

To gather courage, someone began

singing:

“The wide Dnipro weeps and

wails…”

We joined in. I slipped past

checkpoints, made my way down the slope of Instytutska Street. The

southeastern end was deserted, rubble-strewn. On the square side, a

line of shield-bearing protesters was falling back toward the

Millennium Bridge – tilted as if some invisible wind was pressing

against them. Opposite them, from the upper side of the square, troops

advanced in tight columns – four, five across. They fired in bursts,

blindly ahead, as if even they didn’t know who they were fighting. We

could only hope their rifles were loaded with blanks.

A loudspeaker thundered from the

Maidan:

"We need medics at the podium –

urgent! Resuscitation! Four ambulances! As many as you can, boys!"

The square echoed like a furnace

– booming noise, rolling smoke. Gunshots rang out, drowned beneath the

roar. Two protesters were hauling tires onto the bridge. One hurled a

Molotov cocktail into the barricade. Black smoke coiled upward. A lone

bird glided past the golden angel atop the column. Then the crowd

collapsed all at once. Running downhill. Scrambling back.

"Snipers! Two or three in the

Ukraina Hotel!" the loudspeaker bellowed. It sounded like a

twisted broadcast from The Hunger Games.

The bridge was now engulfed in

swirling flame and choking smoke.

That’s when I saw the first fallen body –

limp, like a ragdoll, one arm swinging uselessly. A boy in a blue

jacket was dragging him by the collar, a bright orange helmet flashing

on his head. His shield bobbed awkwardly in front of him – it wouldn’t

have stopped a pellet from an air rifle. Three others flanked him.

After each step, a red stripe froze across the cobblestones. Drag and

drop. Drag and drop. The phrase pounded in my skull. Where are the

shots coming from?! I screamed.

Brother, don’t shoot!

Among the crouched defenders,

someone fell backward. His shield collapsed over him. A gush of blood

leaked out from beneath. The loudspeaker kept begging for medics. Tear

gas burned our throats. Molotov flames leapt higher. More ragdolls were

dragged across the stone. More crimson trails froze beneath them. I

doubled over, gagging. A cold hand touched my forehead. Another braced

the back of my neck.

"It’s okay. You’re okay. Just

breathe." whispered a young woman. "Were you hit?"

"The blood… " I groaned, as she

pulled me under the bridge. "I throw up when I see blood.

The pillar’s icy stone pressed

into my spine. A tracer bullet sparked off a nearby lamp post. All I

could see were her eyes – violet-warm. Her face was wrapped in a

knitted scarf, even her nose hidden. The hat was pulled down to her

eyebrows. She was half a head shorter than me: a violet-eyed samurai

pixie. As she spoke, her breath clouded beneath the pale scarf.

That light-colored outfit – she

was a perfect target, I thought. hat is she even doing here? Only

Ludmilla, my little sister, was missing from this madness...

"Here, drink some tea!" she

handed me a small Coke bottle filled with dark liquid. "I’m going to

help treat the wounded! " she added, then darted away.

"Wait, your tea! " I called

after her.

She waved it off.

"What’s your name? "I shouted

again, but she was already gone." At least show me your face... I

thought.

By nightfall, the Maidan had

fallen silent. The square was in ruins – smoke, soot, ash everywhere.

As if some fire-breathing King Kong had rampaged through – but no, it

was us. God’s restless children, gone blind in rage, left behind this

wreckage. The Berkut and the uniforms had vanished. From above, the

angel guarding our independence looked down without emotion, over the

last glowing barricades… and over the square, now heavy with grief and

reeking of anti-Russian hatred. In front of a burnt-out building,

behind a scorched pillar, a mourning crowd had gathered. Bodies lay

stretched on the ground – once a first-aid point. No more gunfire now,

just sobbing. Mothers and wives crying out. Men crying silently, their

fingernails cutting into their palms. The air stank of death and

scorched rubber.

Five years passed. And that mysterious girl – only her voice and the

color of her eyes returned, again and again, in my dreams.

Much has happened in the world since then. Crimea fell into Russian

hands. War broke out along our eastern border. A civilian airliner was

shot down – maybe by us, maybe not. Maybe on purpose. Maybe by mistake.

The following year, as if on cue, the unlucky half of the world got up

and started walking. Masses streamed westward, chasing the glow of a

rainbow-colored promise. Some were met with cheers. Others triggered

bitter conflicts between nations. Human trafficking became big

business. Behind it, invisible machines, unknown powers. In our region,

we started hearing about black-clad men terrorizing minorities. We

might’ve even torched a church – people hiding there from our own fury.

We became a sovereign nation, rich in natural resources. And yet –

poverty persists. Emigration bleeds us out. Our hope dissolves into

Western illusions.

Something is brewing, people. This won’t end well.

Meanwhile, I finished my degree in IT. Pored over English textbooks.

Built websites. Dreamed in algorithms. And still – my bank account kept

shrinking. One April evening, I sat on a bench along the quay. Leaning

forward. Elbows on knees. Hands clasped. Staring into the Dnipro. A

barge chugged upriver. The port cranes loomed like stork-legged

dinosaurs. Swallows circled above in the cloudless sky. The breeze

carried lilac and the ripe, fermented scent of the river. Somewhere

behind me, a metallic clatter cut through the silence. And then –

Someone sat beside me. A hand rested gently on mine.

"How are you, boy? You survived?

Still sick at the sight of blood?"

The voice was unmistakable. I

turned, breath caught in my throat. I had imagined her face so many

times – her shape, her build – and always got it wrong.

But her eyes…

those violet-warm eyes…

they never left me.

That surprise, the shiver

rushing through my body, the simple warmth of her hand on mine –

those, I’ll never forget.

She smiled. A high forehead.

Rustling, straw-gold hair swept back by the breeze. Thick eyebrows

arching toward her temples. Jawline like the curve of an opening

boomerang. She kept smiling. So beautifully I couldn’t look away.

Maybe Eva Mendes has teeth like

that – slightly forward, bright, too wide for her mouth. I was stunned.

My Dunya – my Dunya – was

Russian. Her full name: Avdotya Romanovna. Say what you will. I don’t

care. I didn’t care then. I never will. Not even if she’s Russian a

hundred times over. We’re young. Adam and Eve. Man and woman.

And if I’m to be the man, then

I’ll do what was written for Adam –

earn our warmth and hearth with the sweat of my brow.

Dunya’s shoulders were broad,

her waist narrow, her hips curved like poetry, her skin soft like silk.

And when, at the peak of our lovemaking, her thighs wrapped tight

around me, and her whole body shuddered, it felt like lava was bursting

skyward. In those moments, I didn’t want to live any longer – because

I’d already been given everything that makes life worth living.

We were planning to move to

England. Settle. Take root. But somehow, we got stuck in Hungary. Or

rather – COVID got us stuck.

Dunya struggled more than I did.

Her job was brutal – twelve hours on her feet at the factory line,

followed by twenty-four hours of so-called rest. She often slept

through that entire day. Woke up foggy, complaining of aching legs or

her back. Fortunately, we had a Hungarian doctor who spoke fluent

English. Dunya described her symptoms. I translated. The doctor

listened attentively, asked sharp questions, explained everything

calmly – though, more often than not, all she could prescribe was rest.

We even began messaging her through Messenger. I’d describe a problem,

she’d reply or call us shortly after. It made a huge difference.

What more could an uprooted

patient ask for? God bless her for it.

One night, just before her

shift, Dunya didn’t get up. She couldn’t. The world slowed to a crawl,

like it was tipping into another dimension. No explosions. No gunfire.

Just silence – dense, invisible, all-consuming. A new era had begun.

Dunya lay there motionless. It wasn’t sleep. It was as if something

alien was holding her captive. Even her skin hurt. She said existing

hurt. I stroked her forehead. It burned. Fever. The bed shook beneath

her. Nearly forty Celsius. I gave her meds, put a cold cloth on her

forehead.

"It’s okay, it’s okay, just

drink some tea " I whispered. But in my mind, I saw Italy. Corpses

lined up in hallways. Nurses crying. Terrified eyes behind oxygen masks.

"Can you breathe? "I asked.

She nodded. Her cough was dry,

violent. Her eyes burned with fever. I called the family doctor. Her

voice came through calm, like from another planet:

"Keep the fever below

thirty-eight. Give her fluids. Cold compresses."

The next day, men in hazmat

suits came. Swabs shoved deep into our sinuses – all the way to our

thoughts. I was only worried about her. Later, the doctor called: we

were both positive.

"How are you feeling?"

"Dunya’s sick. Really sick. Me?

I’m on the edge."

"You’re young and strong "she

said. "You’ll get through this. Fluids. Metamizole. Moist tongue. Keep

calm.

Normally, I’m a calm person. But

this time – no.

"If she coughs blood, or can’t

breathe, or the fever spikes uncontrollably, call me immediately."

"Coughs blood? " I asked.

"It’s possible " she said.

"You’re young and strong. You will overcome it."

Dunya burned for five days.

Coughing fits shook the walls. She barely ate. Sipped only what she

could. On the sixth morning, her temperature was finally under

thirty-seven. She was hungry. Her voice returned. Her eyes began to

shine again.

If relief were a stone on my

chest, that stone would’ve dropped so hard it crushed my legs. Maybe

they’d need amputation.

Maybe I’d limp for the rest of my life – and each step would remind me:

she could’ve died.

But she didn’t.

It took weeks for her strength

to return. Half a year until her sense of smell came back.

But now she was herself again –

Skyping in Russian with her family every evening. "Back home, they

didn’t have enough vaccines. And even if they did, people wouldn’t

exactly line up for them."

My case was mild. A slight

fever. Some coughing. My long limbs ached like hell, but only for a few

days. Compared to what Dunya went through, mine was a hiccup.

The weeks turned into quiet

months. We were simply grateful to have survived. And that, for a

while, we were immune.

Dunya was absentminded at times,

but her mind and heart were always in the right place. She cooked

borscht for me. Made holodets. Tracked down Ukrainians working in town,

and brought them together. It was as if she were wrapping a bandage

around my homesickness.

Her absentmindedness sometimes

drove me crazy – but it was impossible to stay angry at her.

We’d sit in the kitchen. The

window cracked open, letting in the cold February air. The curtain

fluttered. I’d be buried in my laptop. She’d be cooking. The scent of

borscht already curling into my nose.

“How many times do I have to

tell you?! Put the damn net away and come eat! " she scolded me in

Ukrainian.

"Let’s better practice English!

"I tossed back, as I always did, without even looking up.

"Maybe when people across the

ocean learn Russian! "

she snapped, switching to Russian – as she always did when I pushed the

topic. "Who do they think they are? While we were building Blazhenyi,

they were still burning wigwams over Native heads!"

"Well, your dear Stalin’s not

heading to heaven either – after what he did to us with the Holodomor."

I gave the CNN news ticker one

last glance:

“New Ukrainian language law

takes effect. Russian Foreign Ministry calls it a provocation…”

Finally, we sat down to eat. She

dug in with gusto. I was practically drooling just watching her.

"Try mine! "I barked in Russian.

She looked up at me, those warm

eyes wide. Took a spoonful from my plate. Tasted it. Her face softened.

"It’s exactly the same " she

said, surprised.

"I still can’t eat it " I

muttered."

"Why not?"

"Because you didn’t give me a

fucking spoon."

"Ha ha! Oh, right! Well… we’ll

make up in bed. Little Vovochka’s welcome anytime.

We worked. We lived. We loved.

More and more Hungarian words stuck to us. We debated: stay or go?

Dunya wanted to stay.

"I’ll learn Hungarian if I must.

It’s safer here than with the tomyks. The Brits hate Russians."

"So do the Hungarians " I said."

And in my head, I added:

rightfully so.

Then came the email from

Ludmilla:

“Come immediately if you want to

see Grandpa alive. I’ll be online tonight.”

The memory of COVID. The

waiting. The terror. It all returned. I went to my boss.

"I need to leave urgently. My

grandfather is dying."

"Take care on the road " he

said. The news is getting worse. Are you taking Dunya? I wish the world

lived like the two of you do together."

I could hardly wait to see

Ludmilla again – my tiny, delicate little sister.

"Well?! Tell me! " I blurted out

when she finally logged on. She hesitated. Her voice was strange.

"He’s very sick. He’s going to

die."

"Has a doctor seen him?"

"No… He won’t let anyone. Says

he’s lived enough. Says we should leave him be."

"And you… you’re just letting

him?"

"He says: come home. And if you

don’t make it in time, his last wish is this – That we read Robinson.

That we run to the forest. That we learn it. Because something terrible

is coming. The forest will protect us. That’s how he survived the

Holodomor."

"He told me that a hundred times

already. I’ll come. But only for a few days."

"Oh! Good you ask! As for me…

nothing much… except: I’m engaged.

Look at the ring!"

Suddenly Dunya wrapped her arms

around me from behind and whispered:

"Don’t go. I have a bad feeling.

Stay with us. Vovochka wants you to stay too."

And that’s when it hit me. I

was going to be a father.

Still – I wanted to go. I had

to see my grandfather. There was something I needed to tell him. Not

much – just this: I’m going to be a father. And this: I’m okay. Imagine

that, Grandpa – I became self-sufficient. I’m not just surviving, I’m

helping others too. I’ve earned knowledge. They trust me with machines

– real ones. Complex ones. Machines that could terrify you. No, I don’t

need the forest anymore. I’m a city man. Always have been. And I want

peace. With everyone. Even with my old Russian boss from Kherson. Let

him hoard the fruit of others’ labor. Let him pick from stolen BMWs and

Audis. Let him. Karma will take care of it.

Who do I love?

Dunya, Grandpa. Of course she’s

Russian. But you’re wrong: we must reconcile – just like the French and

the Germans did. Besides, Dunya is… so beautiful. So beautiful. And so

–

Dunya held me close and

whispered:

"Stay with us, boy..."

Before I could decide, the

message arrived. He was gone. Guilt tore through me.

Dunya changed too. Her movements

slowed. Her gaze drifted, as if mourning someone she had never even

met. At night she curled up behind me, and I felt Vovochka kicking from

inside her belly.

"Does it hurt? " I whispered,

as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

"No! What are you saying… "she

replied, and I knew she was smiling in the dark.

But by morning, we were both

silent.

At work, tasks piled up on my screen – but I was scrolling through baby

care forums, comparing cloth diapers with premium absorbents. And then

the news flashed across the screen:

“Russian troops have entered

Ukraine. A long convoy of tanks is moving toward Kyiv…”

I froze. Sat there like stone in

the glow of the screen.

Only a hand on my shoulder pulled me back – My boss.

"Go home, Volo. Dunya’s waiting."

She was crying when I arrived.

"What do you want from me? I

wasn’t even there! Do you think it feels good to go from centuries of

speaking Russian…to having my mother tongue turned into a bloodstained

rag? Where’s my justice?!"

Her voice thinned, but her pain

thickened.

"And now that your glorious

language law is punishing us – Don’t forget the Poles. The Hungarians

too. Because now you decide who gets to speak what in their own cities?

And you really think you deserve your own country?"

I said nothing. Sat there with

my elbows on my knees, fingers laced, listening to her bitterness pour

out.

"You know what’s the worst? That

even peace taught you nothing. After '90, there was a chance. You

could’ve chosen agreement. But no – you wanted NATO. Donbas. Missiles.

Pride. What did you think? That a Russian mother doesn’t deserve to

feel safe? And now you’re shocked that someone got fed up?"

Her eyes trembled, but the tears

had dried.

And I…I sat there, listening

like someone trying to decode a foreign language. I couldn’t read her

pain – Not through the shadow of my own.

"You played the big boys. And

it’s fine that you punished me and mine for it? You even killed

Yanukovych. Say what you will, he was ours. One of our boys. He

protected us. You destroyed him – methodically, surgically. And you

expected us not to fight back? That we’d keep our nukes in display

cabinets? Well, here’s your peace…"

We stood still for a while. Then

she turned and went into the kitchen. I quietly followed, but only as

far as the hallway. I couldn’t go in. I watched from the doorway as she

sorted the baby clothes. Bonnets, tiny diapers, knit booties, a teddy

bear blanket were lined up on the counter. She kept folding the blanket

over and over again, as if at least her hands knew what to do. As if

she were already seeking refuge from a world preparing for war again.

“What if it’s a girl?” I asked

quietly. “Will it still be Vova?”

“I’ve known for a long time that

it’s a boy,” she said. “I knew even when there was nothing to see. I

just knew…”

The next morning, when I woke

up, she was already in the kitchen. A bowl of steaming borscht was

waiting on the set table. She was barefoot, her white blouse billowing

softly around her waist, her belly already nicely rounded. The spoon

trembled a bit in her hand, but she smiled.

“Here. For your war wounds. I

made it with cherries this time – just the way your grandfather liked

it.”

I didn’t answer. I opened my

arms. She collapsed into them.

“What can we do? None of this is

our fault.”

“As long as the big boys and the

warmongers keep shoving each other’s heads under the water, all I can

do is make a warm, human bowl of borscht. Stay with us…”“

"We should probably get that

stroller too,” I said. “Little Vova will never put on a uniform…”

We sat down to eat in silence.

I had to go. My work was

waiting. In the shower, a flash hit me: what if a rocket struck right

now? A smart missile I myself might have programmed. Me, with my

knowledge, capable of instructing a weapon: fly there, little genius,

hit that spot – where another Volo, with another Dunya, was folding

baby blankets. Would I be capable of that? Is there that kind of money?

Where would it come from?

The image and thought were so

powerful they made me dizzy. I opened my eyes, but the thought remained.

“At least I’m alive,” I

whispered to myself as the water kept running. And I couldn’t decide

whether that was a relief or a curse.

Dunya’s words from yesterday had

lodged in my soul like shrapnel. She spoke of old wounds we’d never

dared to truly discuss. Slowly I realized how much had remained

unspoken between us – and maybe now it was too late. I felt that hope

had been swept away by a dark, cold tide, and we were just drifting in

it. Some wicked force had crept between us, bitten into us like an

invisible poison, seeping into our love – as if that was where we were

most vulnerable. What once was a refuge had become a battlefield. And

we stood in it – facing each other in the same trench. Only now did I

fully realize what I had long suspected: we had become pawns.

Expendable, interchangeable, insignificant pieces in a cruel game we

didn’t start – but we were paying the price.

And then something broke in me.

Maybe the last of my faith. Or just my patience. I don’t know. But the

words clawed their way out. I turned on myself, silently, inside: What

the hell should I do now? Now… in this wretched situation? Why can’t I

finally be honest with myself? What am I still waiting for? Besides…

what could one even do?

Collaboratte, man! Fairly. No

sneaking, no smartassery. Just… unite. Think. Together. Because this is

no game anymore. It’s here. The climate crisis. That damned COVID, too.

Isn’t this what we should be thinking about? Not who shoots first, or

who’s to blame, or whose missile is bigger. But about what will become

of all this if we keep going this way.

Do we really want to set fire to

our own home? Is this why we climbed out of the animal kingdom? Just to

crawl back now? To destroy everything, then start over – if anything’s

left?

And… aren’t there enough brains,

enough scientists in Russia? Or in that greedy, self-satisfied America?

And China? Just sitting, waiting, silently. Why don’t they sit at the

same table? Why don’t they think about whether this all still makes

sense? Whether… it’s even worth having children on this collapsing

planet?

In the following days, I scoured

the net day and night – Bucha dominated the headlines. I felt like

something was tearing me apart from the inside. My body and heart were

here – my soul and heart were there. One part of me whispered, “Go!”

The other: “Stay!” And both were painfully real. Which was my true

homeland? The one where I was born? Or the one where my child would be?

Both were sacred. But together, they were impossible. And that

impossibility sucked the air out of me – I was paralyzed, unable to

choose.

I was tormented by the need to

decide: over there were my brothers, my past, my language – here was my

love, my child, my new home. Whichever way I turned, it felt like

betrayal. Betrayal of the other. But in the end, time chose for me. War

reached for me like sewage flowing backward through a pipe: I

swallowed, choked, and it swept me away. Days passed, but everything

inside me froze.

Blood poured from the internet,

while at home, my love folded Vovachka’s blanket. Which finger should I

bite?

In the end, I didn’t choose –

the war chose me: it swallowed me whole. I slipped into my fatigues

without realizing.

It was late summer when I

returned home and signed up as a volunteer. I ended up in boot camp –

training went on 10-12 hours a day. I never imagined how hard a

Kalashnikov kicks. Then I was assigned to the IT systems of American

heavy weapons. I was in charge of missile guidance. “Yes, sir,” I said.

I worked diligently, precisely – “solid work,” they said. They trusted

me. Didn’t ask about my past. Didn’t know about Dunya…

One night I dreamt Vovachka was

crying, and Dunya cooed to him in Russian. I didn’t understand any of

it.

Sometimes I scrolled through

Messenger or played her voice messages:

“It’s baby formula, you idiot,

not gunpowder!”

“Kiss me, boy…”

“You really left me alone during

labor?”

“It’s raining, we’re waiting –

they haven’t started the heating yet.”

“Come home. We’re waiting.”

I hadn’t replied in weeks. Even

silence had become a weapon. So had forgetting.

One morning, as I buttoned my

combat uniform, I looked into the mirror. A bearded, hollow-eyed

stranger stared back. I nodded to him: Let’s go. Back to work.

By mid-November, we’d retaken

Kherson. We let off victory salvos, even though we were down to our

last shells.

We roamed the ruined streets –

the devastation was indescribable.

The horror of burnt-out wreckage

mounds.

The sorrow of bombed-out

buildings with gaping, wall-less facades.

The angry sadness of balconies

about to collapse.

The howls of skin-and-bone,

red-eyed stray dogs with tails tucked between their legs.

In front of a shelled,

near-collapsed apartment block, someone stood. Back to me. Like a

statue. I didn’t know all the uniforms yet – he must’ve lived here, I

thought. But as I got closer, I saw the white-blue-red armband on his

left arm. And I opened fire. Reflex and rage. My first shot at a living

human being.

He spun around. Grabbed his

shoulder as he fell. The world cried out. Blood bubbled from between

his fingers. My sergeant stood over him, legs apart.

“Nice shot,” he said, watching

him twitch.

Then, slowly, he unlocked his

machine gun. Shot the left foot. Then the right shin. Then the thigh.

Then the chest. But by then, the young soldier with the narrow mouth

had stopped moving. Mouth open in a scream, dead eyes staring at the

flock of crows circling the November sky.

My sergeant stepped aside from

the steaming pool of blood creeping toward his boots. He leaned over

the body. Fished through the pockets. Pulled out a blood-soaked leather

wallet. Slowly opened it. “Private Vladimir Romanov,” he spat with

disgust. “We don’t take prisoners,” he added. “The bastard was planning

a wedding – may he never find peace, not even in the grave.” He held up

a photo.

The picture showed a boy with

violet-blue eyes, a narrow mouth, smiling with a prominent set of

teeth, sliding a ring onto my sister Ludmilla Piatkina’s finger. He had

teeth like that Latin American actress – can’t remember her name right

now.

In my recurring dreams, a fleet of enormous sky-vehicles appears above

our city, hovering just a few hundred meters above the rooftops. They

move slowly and silently, like cigarette smoke curling in still air.

They block out the sun – the landscape darkens under them. From their

shimmering mercury bodies, tubular, coiling, flashing devices extend

toward the ground. Groups of frightened people

stare skyward, petrified. Others drop to

the ground, hands clasped behind their heads. “We urge the population

to remain calm,” booms a thunderous voice across the square. Then beams

of light shoot from the machines toward the buildings – leaving

golf-course-sized, city-block-wide black, smoking craters where they

strike.